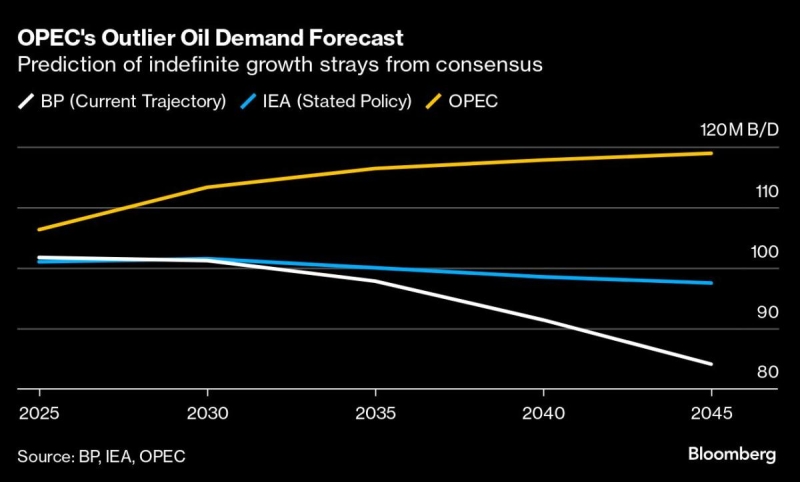

(Bloomberg) — OPEC doubled down on forecasts that global oil demand will keep growing to the middle of the century, an outlier view that scientists say would lead to climate catastrophe.

Most Read from Bloomberg

World oil consumption is set to increase by 17.9 million barrels a day, or roughly 18%, to 120.1 million per day by 2050, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries said in its annual long-term outlook. It raised estimates covering the next two decades from last year’s report.

Even within the petroleum industry, OPEC’s estimates represent a fringe view-point. Forecasts from BP Plc, trading giant Vitol Group, Goldman Sachs Group Inc., consultants Wood Mackenzie and the International Energy Agency all indicate that oil demand may stop growing within the next decade as the world shifts to electric vehicles and renewable energy.

The cartel, led by Saudi Arabia, has acknowledged the dangers posed by global warming and argued that the oil industry should be part of the solution — even attending the COP climate summit for the first time last year. Yet its flagship report provided little detail on how carbon capture — its favored solution for fossil fuel emissions — can overcome the significant technical and commercial hurdles to mass adoption.

OPEC said its increasingly bullish outlook reflects that, in light of the 2022 energy shock, advanced economies are re-evaluating the transition from fossil fuels as they acknowledge “the need for energy security.” At the same time, developing nations are pushing for access to affordable fuels, according to the report, which was compiled by OPEC’s Vienna-based secretariat.

By 2030, world oil use will increase by 11.1 million barrels a day to average 113.3 million per day, it forecast. That’s 1.3 million a day more than in last year’s outlook, which had raised estimates from the previous year.

India will be the single-biggest contributor to growth, adding 8 million barrels a day by 2050, more than three times the increase projected for China, OPEC said. Petrochemicals, road transport and aviation will drive the global expansion, and by 2050, cars with internal combustion engines will still compose more than 70% of the fleet.

Yet such predictions are incompatible with international climate goals. To limit temperature increases to 1.5C, the world must immediately and drastically reduce oil consumption, and halt investment in new oil and gas projects, the Paris-based IEA contends. If demand keeps increasing to 2050, temperatures may rise by 2.5 to 3 degrees, according to researchers at Imperial College London.

The risks posed by a warming planet were made clear this year, from a deadly heat wave in India to devastating floods across Africa and Europe, and wildfires from Greece to Brazil’s Amazon rainforest — and even the Arctic tundra. OPEC members themselves have often been on the receiving end, with record heat in Saudi Arabia killing more than 1,300 pilgrims, floods inundating Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, and the power grid pushed to breaking point in Kuwait.

The report predicted that OPEC and its allies will be able to keep increasing supplies through to 2050, holding their share of world total liquids supply broadly steady at 52%. It said the notion of phasing out oil and gas was a “fantasy.”

Yet, in May, OPEC Secretary-General Haitham Al-Ghais formally participated in talks ahead of the COP29 conference in Baku, Azerbaijan, urging the oil industry to offer “solutions to the climate challenge.” The outlook assumes that emissions will be limited by a “rapid expansion” of projects to capture and store carbon dioxide, a technology that experts consider unproven and expensive.

The credibility of OPEC’s long-term outlook isn’t being helped by its short-term forecasts.

The cartel continues to project that demand will surge by 2 million barrels a day this year, considerably more than expected by Wall Street giants like JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup Inc., and even at the upper end of the range anticipated by state-run giant, Saudi Aramco. OPEC’s forecasts are belied by faltering crude prices, which have lost about 13% since early July to trade near $75 a barrel in London.

Even the group’s member nations have shown a lack of confidence in its bullish assessment, choosing to delay the restart of halted production by two months until December amid concern that demand remains too fragile to absorb the extra barrels.

Most Read from Bloomberg Businessweek

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.