The start of the Federal Reserve's rate cuts last month was expected to bring bond yields down—and take some pressure off the spiraling U.S. debt burden.

Last month, Apollo Global Management chief economist Torsten Sløk noted that with U.S. debt now at $35.3 trillion, interest expenses average out to $3 billion a day. That's up from $2 billion about two years ago, when the Fed began its rate-hiking campaign to rein in inflation. At the time, he had hope for the anticipated Fed rate cuts.

"If the Fed cuts interest rates by 1%-point and the entire yield curve declines by 1%-point, then daily interest expenses will decline from $3 billion per day to $2.5 billion per day," Sløk estimated.

So far, it's not working out that way.

To be sure, Treasury yields tumbled ahead of the first rate cut as investors looked for an aggressive easing cycle to match its aggressive tightening cycle.

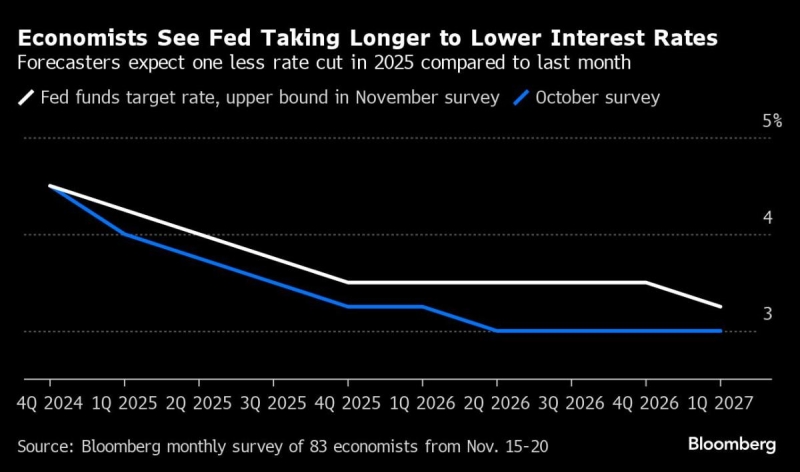

But since the Fed's policy meeting wrapped up, yields have jumped, and some Wall Street forecasters have warned that the central bank may even pause on further cuts.

That's as Fed officials and economic data have dampened optimism for many cuts. First, policymakers’ so-called dot plot of projections on rates tilted toward slightly less easing than the market anticipated.

Then, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell said at the post-meeting news conference that the jumbo half-point cut wasn’t necessarily indicative of the pace of future cuts. A week after that, he cautioned that Fed officials are in no hurry to cut rates further.

Then last week's blockbuster jobs report pointed to a still-robust economy that needs of plenty of workers who are demanding higher wages. And finally, the latest consumer price index report showed inflation is cooling but is a bit stickier than expected.

As a result, the 10-year Treasury yield has jumped about 50 basis points from before the Fed meeting to Friday and is now almost 4.1%. The 2-year Treasury isn't much better, having jumped about 40 basis points in that span to about 3.95%.

Those yields affect the Treasury Department's auctions of fresh U.S. debt that are needed to cover massive budget deficits, which are also driven in part by the rising expense of servicing U.S. debt.

For the federal fiscal year that ended on Sept. 30, the budget deficit was $1.8 trillion, and the interest expense on U.S. debt was $950 billion, up 35% from the prior due mostly to higher rates.

Treasury yields could go back down again, especially if the labor market shows signs of significant weakening. But even if Fed rate cuts lighten the burden on interest payments, the next president is expected to worsen budget deficits, adding to the pile of total debt and offsetting some of the benefit of lower rates.

In fact, a recent analysis from the Penn Wharton Budget Model found that the deficit will expand under either Donald Trump or Kamala Harris. Under Trump’s tax and spending proposals, primary deficits would increase by $5.8 trillion over the next 10 years on a conventional basis and by $4.1 trillion on a dynamic basis, which includes the economic effects of fiscal policy.

Under a Harris administration, primary deficits would increase by $1.2 trillion over the next 10 years on a conventional basis and by $2 trillion on a dynamic basis.

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com